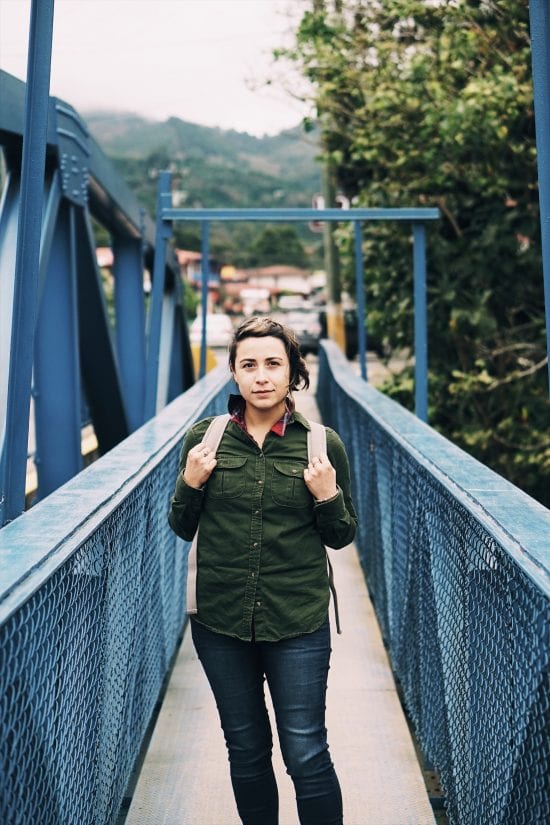

Lucia Solis believes fermentation can not just improve coffee, but give control to farmers. In this interview, we learn how fermentation has the potential to change the coffee industry.

BY ASHLEY RODRIGUEZ

BARISTA MAGAZINE ONLINE

How do you describe “fermentation” in coffee? If you’re unsure, ask Lucia Solis, a fermentation designer and consultant at Luxia Coffee Solutions. A former winemaker, Lucia first turned her attention to coffee when wine harvest season was over, and now she works with farmers and mills all over the world to improve coffee quality and give control back to producers.

Ashley Rodriguez: Can you tell us about your first coffee memories? Did you grow up with coffee in your life?

Lucia Solis: Even though I was born in Guatemala, I did not grow up near or around coffee. My first memory of coffee was in high school; my mom is a coffee enthusiast, and as early as I can remember, she would make her own lattes at home and take the process very seriously. If we were going somewhere for even a weekend trip, she would bring her espresso machine. I associated coffee as a large part of her identity, and being a rebellious teenager, I made it part of my identity that I did not drink coffee.

I kept it up for a long time. I didn’t become a regular coffee drinker until after I turned 30, and even then I had to set an alarm on my phone every day to remember to drink coffee. It would be like 11 a.m. and I’d hear a buzz for a notification and I’d think “Damn! Forgot to drink coffee again.” My first true love is science, and that’s how I approach coffee.

AR: How did you get into coffee fermentation? What career choices led you to your current position?

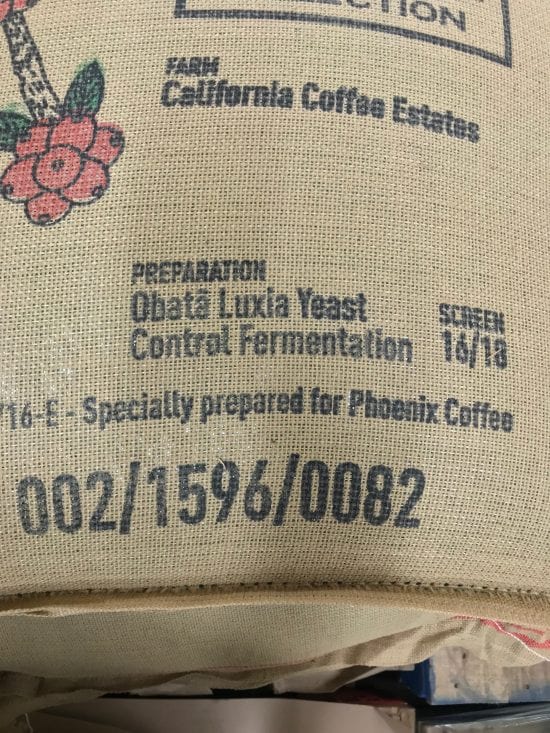

LS: I grew up in Northern California and graduated from UC Davis’ Viticulture and Enology program. It’s a combination of the microbiology and chemistry of winemaking. I went straight to Napa Valley and worked in wine production. In 2014 Scott Laboratories, a major supplier of yeast to the wine industry, hired me to expand their wine industry in Baja Mexico. At the time, they had already started working on testing coffee fermentations and yeast strains. The coffee and wine harvest are opposite schedules, so when the wine harvest was over, they sent me to Central America with yeast in a backpack to work at various wet mills. I still did not drink coffee; nothing about the coffee industry was even on my radar.

AR: How did your interest in fermentation processes start?

LS: My love of science started in high school. I had fantastic chemistry and biology teachers that made experimentation fun and opened up a whole world for me. When I was 15 I was pretty sure that I would work in chemistry. Then when I was 16 we had a class where we learned about fermentation by brewing our own beer; part of the grade was determined by flavor, and the poor grad student who had to grade us had to suffer through some very nasty beverages. Early on I got the chance to connect science and living organisms and flavor.

AR: How do you begin to explain fermentation and the work that you do when the term “fermentation” is so loaded in coffee as it is?

LS: I would say coffee has the opposite problem. It’s been my experience that the term “fermentation” is not loaded enough. To most coffee producers it’s just a simple step during coffee processing where the sticky fruit pulp is removed, and many think it’s inert. I think now many consumers are connecting it with health or flavor results.

To science, it’s a metabolic process, it’s how microorganisms (like yeast and bacteria) obtain energy. I think the issue is that almost everyone I talk to has their own definition of fermentation, and we have not all agreed on a meaning. We think we are talking about the same thing because we use the same word, but I see so many misunderstandings. For example, I’ve been surprised by how many people don’t know that coffee comes from a fruit; many think that it’s a legume because we call the seeds “beans.” So I think language and how we communicate is a big part of the barrier.

AR: How do you use fermentation to solve issues on coffee farms? Where do you begin your work and how do you think about prescribing solutions?

LS: I begin by listening to my client and getting to know the situation at their mill because every location is a little different and each producer has their own resources and challenges. In some places they have abundant water but lack labor. Other places they lack water but have abundant sunshine during harvest and can have slow sun drying.

My favorite part of using fermentation to manage coffee processing is that it’s a versatile tool. You can use it to achieve opposite goals such as shortening or lengthening fermentation. For example, if you are a producer who has a mill in a very cold location and it takes 72 hours to remove the mucilage, I can work with them to reduce that time and make the process more efficient. A second producer could have their mill in a much hotter climate and they could deal with defects that lower quality in as little as 12 hours; I can work with them to extend that time. I can make the time longer or shorter; we can intensify the flavors or perhaps make a more neutral/mild profile.

AR: What is the most rewarding part of your work?

LS: The best part is empowering coffee producers to have a larger say in their own product quality. In so many places the perception of quality has been predetermined by the market. Coffee producers play a lottery of sorts. Some are lucky enough to have a coffee farm in Ethiopia with heirloom varietals on a mountain at 1,900 meters above sea level (masl) with perfect weather. Others are not so lucky and have a farm at 1,000 masl in the plains of Brazil.

Without tasting the coffees, many have already decided the quality and what they would pay for these. It’s a backwards system where the market decides what we are willing to pay for coffee versus what producers are willing to sell for. I believe both of these places can make good coffee if they have access to the tools.

AR: What do you wish people knew about fermentation that they don’t?

LS: If I could have a billboard, I would use it to say that all fermentation is anaerobic by definition. Calling a fermentation “anaerobic” is scientifically redundant. Even a fermentation in open air is still anaerobic because it refers to the metabolism of the microbes independent of the environment that they are in.

It’s a shorthand to describe a style of processing that some people use, but I have seen many different things fall under this large umbrella and it’s misleading. Its a coffee colloquialism that is masquerading as a scientific term.

AR: Where do you see the future of fermentation going?

LS: This is a neglected part of the coffee industry, but it’s very well developed in other beverage industries like beer and wine. I see the future of coffee catching up to those industries in knowledge. Success to me will be when it’s so common, we barely talk about it.

AR: What do you want people to know about you?

LS: Due to the nature of my work, many people incorrectly think I am in academia. I am a consultant for private clients, not a researcher. I design fermentation experiments not as research but to solve problems for my clients. I’ve worked in mills in 13 countries and 35 different mills; I’ve seen many scenarios and believe that almost everyone could benefit from understanding a little microbiology to improve quality.