Visiting a coffee plantation is a unique experience for any coffee lover, and an opportunity to learn more about what’s behind a coffee bean.

BY TANYA NANETTI

SENIOR ONLINE CORRESPONDENT

Photos by Tanya Nanetti

Ever since I fell in love with specialty coffee, I have always wanted to visit a real coffee farm. Sure, years ago I had been to one of the big tourist farms on the Big Island (Hawai’i) and had also visited a small coffee plantation in the Kintamani region of Bali, but this time I wanted something more special.

Using the most of my time in Central America, I tried to find a coffee plantation to visit. I wanted something sustainable, run by nice people, producing coffee that I had already tried and—most importantly—that I had found delicious to drink.

Just a couple of weeks before my departure, the opportunity came out of the blue. In my shop, I had a perfect Costa Rica roasted by Sumo Coffee Roasters. After the first sip, I couldn’t stop drinking it.

I immediately contacted Daniel Horbat (owner and roaster of Sumo) and asked if he could put me in touch with Diego Robelo, general manager of Aquiares Coffee Farm in Costa Rica since 2017. Two weeks later, on a sunny spring morning, we were in the mountainous region of Turrialba in central Costa Rica, ready for an exciting day at Aquiares.

At 9 a.m. sharp—along with a group of students from a U.S. university—we were greeted by a couple of Aquiares team members. Our day started with a nice walk on the coffee farm. Strolling through the coffee fields to the viewpoint, we had our first chance to get to know Aquiares better.

Aquiares, which means “the land between the rivers“ in the indigenous Huetar language, is more than just a coffee farm. Back in 1890, when its founder bought the land, he decided to build houses next to the coffee fields for people who would join the community. Community, along with coffee (of course) and conservation (of the land), is still one of the pillars of the farm.

Our first stop, on the way up to the viewpoint, was a small greenhouse. Here, as in many of the larger greenhouses scattered around the farm, the first stages of growing a coffee plant were taking place: Seeds were scattered and then covered with banana leaves to maintain the right conditions for their germination.

For the next six months, community women would care for the small plants until it was time to transplant them into open fields. After two years, the plants will be productive and remain in the field until they are 25 years old (although a coffee plant can live up to 100 years). They will then give way to new, more productive plants.

Arriving at the top of the hill after a steep walk, under the ancient capu (ceiba) tree that dominates the entire valley—sacred to the indigenous people who lived here—we could see for ourselves how big Aquiares is. It’s the largest coffee farm in Costa Rica, and with 600 hectares of shaded coffee plantations surrounded by 200 hectares of protected rainforest, Aquiares is also a proven model of regenerative agriculture.

The trees surrounding the coffee plantations have several essential functions. They help produce oxygen, they are carriers of new seeds that can encourage the spontaneous growth of other trees, and they can help add specific nutrients to the soil (as in the case of the poro tree, which helps add nitrogen).

In addition, the forest shade helps protect the coffee plant from the open sun, slowing the ripening of the coffee cherry, which will then be bigger and tastier.

At that point, with tropical storm clouds rapidly approaching, it was time to return to the main office and meet Diego, who took over the tour. He explained the three pillars of the farm (community, coffee, and conservation), and shared interesting facts about coffee and the farm itself.

Located in the rainy, Caribbean side of Costa Rica, Aquiares has a climate perfect for promoting abundant coffee blooming (up to 14 blooming seasons per year). As a high-altitude farm, it’s ideal for growing high-quality coffee plants. The acidic soil helps grow coffees with more intense acidity; the thicker pulp helps protect against the cold, creating fruitier flavors; and the mucilage provides floral notes. In addition, coffee here is made strictly of hard beans, with higher density, which helps develop better flavor.

As for coffee production, until a decade ago Aquiares only grew commercial coffee. That started to change in 2013, with their first successful crop of specialty beans. Working with specialty coffees allowed Diego and his team to start experimenting more; new varieties, new processing methods and fermentations, and funky micro-lots processes take place in a separate micro-mill.

Stay tuned for part two of this article at Barista Magazine Online.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Tanya Nanetti (she/her) is a specialty-coffee barista, a traveler, and a dreamer. When she’s not behind the coffee machine (or visiting some hidden corner of the world), she’s busy writing for Coffee Insurrection, a website about specialty coffee that she’s creating along with her boyfriend.

READ THE LATEST BARISTA MAGAZINE

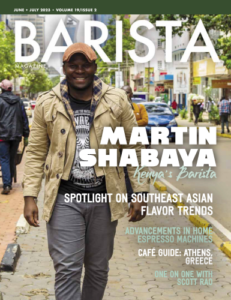

Out now: It’s the June + July 2023 issue of Barista Magazine featuring Martin Shabaya of Kenya on the cover. Read it for free with our digital edition. Get your Barista Magazine delivered; start a subscription today! Visit our online store to renew your subscription or order back issues.