This short but detailed book gives readers a deeper understanding of some important and misunderstood aspects of coffee growing and trading.

BY TANYA NANETTI

SENIOR ONLINE CORRESPONDENT

Photos by Tanya Nanetti

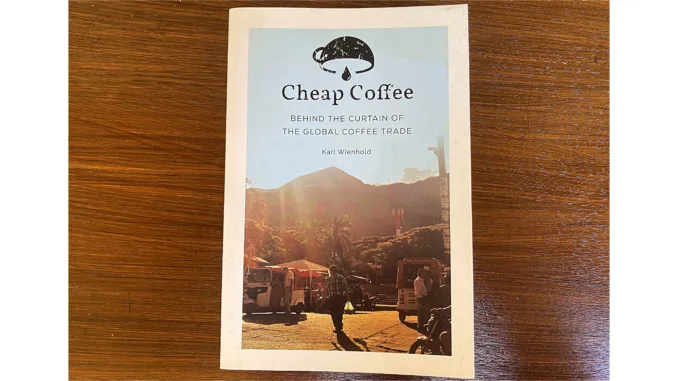

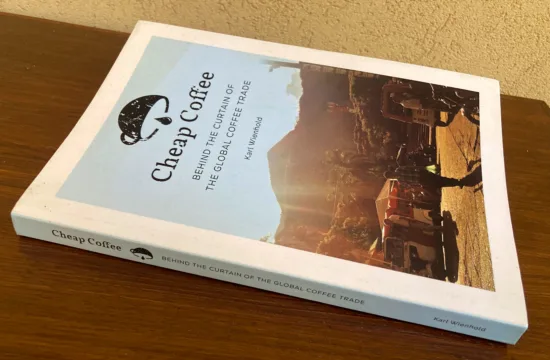

I met Karl Wienhold some time ago while working at my last coffee shop. He came in for coffee and stopped by after closing for a long chat about all that goes on behind that simple cup of coffee: the economy, the trade, the players involved, and the big and small problems that plague coffee producers around the world. Karl took the opportunity to introduce me to his book, “Cheap Coffee: Behind the Curtain of the Global Coffee Trade,“ sharing his reasons for writing it.

“I’ve been fortunate to spend a lot of time absorbing a lot of the available information about the coffee trade and the different sides of the many debates about justice and sustainability, and to participate in them at all levels, from farm to consumer, for over a decade,“ Karl said. “In conversations with people from both the consumer and production sectors, it seemed to me that there was a lack of empathy and understanding of the constraints and needs of the other side that prevented deeper collaboration. Thus, I tried to consolidate much of what I had learned and read elsewhere into a short, semi-encyclopedia-style volume that people who have to spend most of their time making coffee could digest relatively quickly and hopefully be inspired to delve deeper and explore some of the many references cited.“

This introduction was enough: I was determined to read “Cheap Coffee“ to understand more deeply the cup of coffee I was brewing and drinking every day. When I received my copy, I discovered one of the most complex and thought-provoking coffee books I have ever read.

Cracking Open ’Cheap Coffee’

“What’s behind your morning cup? One question first. How much do you really want to know? Do you want to know how the sausage is made? Once you understand how all this works you may no longer be able to consume your preferred coffee brand with a clear conscience.“

These three opening lines immediately alerted me to the consequences of continuing to read “Cheap Coffee.“ While not an overtly political book, as Karl says in his introduction, it will ruin “any tidy, simple, black-and-white interpretation of how the coffee business, and international supply chains in general, function,“ giving readers a broader understanding of some of the most important and misunderstood aspects of coffee growing and trading.

Karl goes on to specify how his book is not about “how to save coffee,“ but intends to share analysis of proposed solutions, theories, and projects being pursued. It’s technically not just about coffee, but “a case study about globalism and post-colonial rural development.“ And, just before the first chapter, Karl simply explains what is wrong with cheap coffee: “If coffee is both good and cheap, it’s probably because a producer was swindled.“

Economics Intro

The first part, “Introduction to Coffee Economics,“ begins by explaining why coffee is a good case study (it is a large market, affects many humans, and happens in many places), and goes on to explain key concepts of economics and theories of economic development. Covering topics such as utility and price theories, perfect and imperfect competition, neoliberalism, the idea of commodities, and so on, most of the chapter introduces economics in general, while including some interesting concepts closely related to coffee, such as the explanation of elasticity or “how much price fluctuation buyers will absorb until they change buying habits.“

With regard to coffee, studies say that consumers are rather inelastic: In practice, if someone drinks three cups of coffee a day, they will probably continue to do so in most cases, even if the price of coffee increases or decreases. Even when personal income changes, there will likely be adjustments in coffee-consumption habits, but not in the amount of coffee consumed.

Value Chain

The second part, “The International Value Chain,“ once again deeply rooted in economic concepts, focuses on everything related to the coffee supply chain, starting with a brief explanation of the meaning of the term. Then Karl moves on to the power of large retail chains and consequently large roasters, which in turn can influence traders in their search for ever-cheaper green coffee. This often leads to competition among producing countries, where only the cheapest will survive.

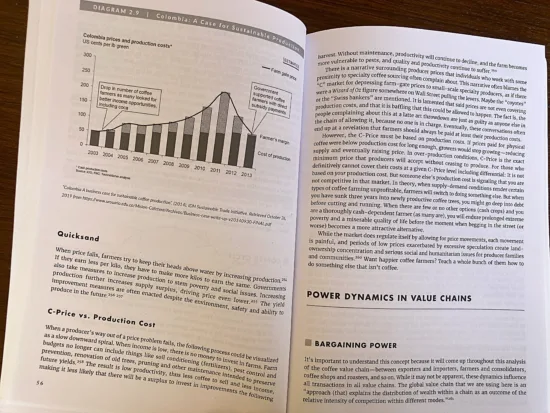

After explaining how roasters act, it is time for Karl to analyze the position of the other players involved in coffee (from producing countries to traders/importers, governments and regulators), to talk about the price of coffee (with the help of interesting diagrams that effectively show concepts such as the distribution of income among different actors), and to analyze the value chain, addressing interesting concepts such as the “race to the bottom,“ which is increasingly lowering the cost at origin.

The last pages of the chapter are specific to specialty coffee and are somewhat painful to read, as they describe the contradictions and difficulties of this market, especially in the countries of origin.

On the Farm: Production, Labor, Profit

As the name suggests, the central chapter “The Farm“ ties in with the end of the previous chapter by covering all aspects related to the farm: the different products, the cost of production and labor, profitability, and all issues related to the self-sufficiency of the farm. It is an interesting section that moves a bit away from pure economics to explain the important and essential reality of coffee, so different from our daily experience.

Environmental Concerns

The fourth chapter, “Sustainability,“ concentrates on sustainability, providing an overview of all the challenges facing small coffee farmers, covering social, economic, and environmental issues. It is perhaps the easiest part to read, due to the lack of big numbers, diagrams, and calculations. Yet it is probably the most effective and realistic, with its narrative throwing the reader right into the middle of a small coffee plantation, learning about all its struggles to survive in the tough coffee business.

The final chapter, “The Solutions: Hits and Misses,“ explores a range of topics related to possible solutions to “improve“ the coffee trade, including price control, profitable farming, direct trade, and more.

Of particular interest is the holistic solution offered, which proposes a broader way of approaching the quest for a sustainable coffee production sector through a series of actions and a new way of thinking.

To conclude the book, Karl chooses to include some simple anecdotes, sharing the powerful stories of three coffee farmers he met through his organization, the Cedro Alto Coffee Farmers Collective, which supports the empowerment of small Colombian coffee farmers.

It is a perfect way to conclude “Cheap Coffee,“ in a way putting a face and a name to all the theories and practices explained up to that point.

The Takeaway

“Cheap Coffee“ deals in economics and lots of theory that may be difficult for the casual reader. The concepts are nevertheless made simpler by examples and diagrams; there are hard, illuminating truths and some proposed solutions. While “Cheap Coffee“ is not an easy book to read, if one takes the time to read it carefully, it will surely change the way one views coffee, giving a new awareness toward it and economics in general.

Best read with an open mind (and a willingness to change things), this is a tough book that prompted me to ask Karl whether things in the coffee industry are changing or will change, and to what end.

“Inevitably things are changing, for the worse and for the better, I’m sure,“ Karl shares. “Those who have no interest in sustainability are finding increasingly clever ways to confuse consumers and make themselves look good at the expense of those who are actually working for change.“

It’s not all bad news, however. Karl adds that “there seems to be a passionate cohort in both producer and consumer communities who are curious and thoughtful and unafraid to acknowledge the ugly parts of the past and how they create the present, particularly how marginalized groups have been silenced and subordinated. … I see this as an insufficient, absolutely necessary, and encouraging first step toward finding more equitable ways for individuals running the coffee trade to do business together.“

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Tanya Nanetti (she/her) is a specialty-coffee barista, a traveler, and a dreamer. When she’s not behind the coffee machine (or visiting some hidden corner of the world), she’s busy writing for Coffee Insurrection, a website about specialty coffee that she’s creating along with her boyfriend.

Subscribe and More!

Out now: It’s the June + July 2024 issue of Barista Magazine! Read it for free with our digital edition. And for more than three years’ worth of issues, visit our digital edition archives here.

You can order a hard copy of the magazine through our online store here, or start a subscription for one year or two.