In this series on Barista Magazine Online, coffee producers talk about what a low C-market price means to them.

BY KENNETH R. OLSON

BARISTA MAGAZINE

The global commodity market for coffee has recently fallen to a 12-year low, dropping below $1.00/lb. and in many cases falling below the cost of production for coffee farmers. At the World Coffee Producers Forum in September, Roberto Velez CEO of the Colombian Coffee Growers Federation (FNC), said, “It is today a desperate moment for the 25 million coffee growers around the world. It is a crisis beyond imagination.”

At the same event, Rene Leon Gomez, the executive secretary of Promecafe, which is based in Guatemala and represents many Central American coffee farmers, said, “I would say millions of producers in the region are desperate right now. A lot of farms are being abandoned, social conditions have deteriorated.”

With these dire warnings in mind, and with the well-being of coffee farmers and the future of our industry weighing heavily on our hearts, we wanted to talk to some specialty-coffee producers from around the coffee-growing world and ask them what a low C market means to them, how it affects their farms, and what kind of an impact the collapsing C has on their communities.

We have more coverage on the C market in the December 2018 + January 2019 Issue of Barista Magazine. Chris Ryan writes about the C market and why it’s important even to specialty producers in “A Volatile Presence: Understanding the C Market and How It Works.”

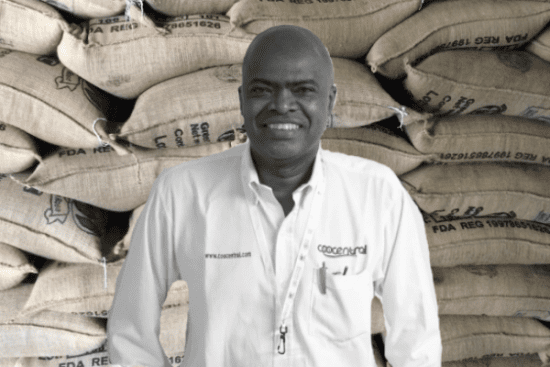

In this series, we hear directly from producers about how the low C impacts them; in this installment, we talk with Emel Mosquera Rivas from Colombia.

Emel Mosquera Rivas is the lead coordinator for coffee at the Coocentral co-op in Huila, Colombia. The Coocentral cooperative has some 4,000 members. All of them grow coffee as their primary source of income. More than 90 percent of their coffee is specialty grade. All of it is also certified Rainforest Alliance, Utz, and more.

Emel is friendly and gregarious, and he is happy to talk about his co-op, their community, and how the C market impacts them. From time to time, to make a point, he’ll ask me to stop taking notes and just listen.

Emel says he sees the effects of the falling C market when members at co-ops in Colombia become reluctant to sell their coffee at the mill. He says Coocentral avoids some of this because of their certifications and their specialty level of production, which generates higher prices for their members. “[When] members stop selling coffee, they hold onto the coffee waiting for a better price. When they do that, they lose quality,” and then they get an even lower price, he says, creating a vicious circle.

At Coocentral, he says, they try to avoid that by offering the best prices around. They will also buy one part of a farmer’s crop at a time to help protect them against hitting an even lower price in the future if the farmer tries to hold out for a C-market rebound.

But fundamentally, Emel says, “The whole economic situation goes down.” And since coffee is the primary source of income for so many people in the community, when farmers generate less revenue, “all the other economic areas also go down,” he says.

To help mitigate some of the uncertainty of the C market, Emel say, the co-op buys coffee futures to protect against low prices. But that doesn’t always help. “Last year everyone thought the market would go up,” he says, “but it didn’t, and it’s just going down.”

With a falling C, Emel says, “The certifications help a bit. But those certifications are still tied to the C market.” He also says the co-op has some fixed-price contracts (contracts with buyers that have prices that are not tied to the C market), but “they only help a little bit” since those contracts represent only a fraction of the co-op’s production.

“It’s kind of a crisis in the community,” he says, adding they didn’t see it coming. “It’s complicated,” Emel says.

At the root, Emel says, for his coffee-growing community to thrive, “It needs to move away from the C price. How can it be that a roaster comes down and says your coffee is worth is $1, but why?” His eyes go to the ceiling and he makes the sign of the cross.

“If it continues the way it is right now, it’s going to get to a point where producers are going to say they’re not going to do this any more. We need to find a balance. Everyone needs to be able to live comfortably, or it’s not going to last,” Emel says.

Simply put, Emel adds, “When the price goes down, quality goes down.” He says at the co-op they tell the members, “Be sure that you’re keeping up the quality because if you keep up the effort you’ll be able to sell at the same price.” All of their established relationships (with roasters) pay the same price as before because they see the same quality, he says.

As of now, Emel says, he hasn’t seen any of his members give up on coffee farming, but he says, “People are frustrated, and it’s hard to keep going, but that’s what the coop is for. To support people when they’re struggling.”

Emel also believes that if more coffee professionals had the opportunity to visit origin, they would be incentivized to pay higher prices to support coffee-producing communities. “If they visit Huila,” Emel says, “they fall in love, [and] because if they’re in love they’ll help, and they’ll want to pay good prices.”