There are countless articles and pieces on the effects of climate change on our world. In the first part of this ongoing series, we break down the realities of climate change as it relates to our industry, looking at how it will fundamentally transform the way we grow and drink coffee.

BY ERIKA VONIE

BARISTA MAGAZINE ONLINE

There is an inherent clench-and-release reaction whenever an article focuses on the words “global warming.” The overwhelming notion of our planet heating up can be understood in catastrophic detail. Constantly a source of debate, these words pop up in the news on a near-regular basis. Just recently, the world reeled from the United States backing out of the Paris Agreement, which is a coalition of 195 countries each determining their own contribution to mitigate global warming. As much debate and discourse as there is on this matter, the facts are clear: The world is getting warmer, and it is affecting us all.

Clearly, global warming’s most visible impact is on an environmental level. We all know coffee requires cellular respiration—hot, sunny days and cool nights. Because of unpredictable rainfall and rising temperatures, places in Central America, like Nicaragua specifically, predict that by 2050, 80 percent of current growing areas will no longer be usable. The mean optimum altitude for growing across Central and South America will rise 200 meters by 2020 and 400 by 2050. This is because the ideal regions for optimum production need to meet the demands of respiration.

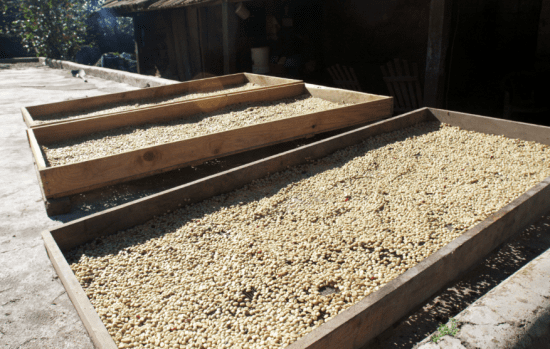

Jacob Elster, co-founder of Crop to Cup Coffee Importers, adds: “Erratic rain patterns lead to multiple flushes, making harvest more difficult. Moreover, you are supposed to apply different treatments to trees depending on whether they are in flower or cherry. When you have both at the same time, and don’t know when to expect what, even those who have the treatments and manpower to apply them have a hard time doing so properly.” Some farmers estimate that they would have to revisit the fields for a harvest eight or nine times in the season, because of staggered cherry ripening. Again, the explanation as to why this is taking place is said to be due to irregular rains and mild winters.

World Coffee Research recently released a piercing statement about Lempira, a hybrid cross between Timor and Caturra, falling susceptible to Roya in Honduras. Lempira was touted as being a high-yield rust-resistant cultivar, a beacon for farmers after a Roya epidemic hit Central America in 2012. This is particularly troubling for thousands of farmers across Honduras who planted Lempira in the wake of this epidemic. This crippling disease—also known as coffee leaf rust—ruins coffee production, and records have shown it has reduced coffee production as much as 20 percent each year for the last three years in Central America.

Aleco Chigounis, founder of Red Fox Coffee Merchants, has seen firsthand the devastating effects of Roya: “… We see folks in Puno, Peru, who have gone from producing 10-15 bags annual of parchment only a few years ago now only producing 3-5 bags. Roya has smashed them.”

Another less visible but arguably more important victim of global warming is the farmer. Farmers suggest that the coffee plants are “confused”; the erratic climatic cues are eliciting different phenological (the study of cyclic and seasonal natural phenomena) responses from the plants. This is a two-pronged predicament; farmers must spend more money to have migrant workers for longer periods of time while harvesting less coffee. Furthermore, many farmers live far enough away from the co-op that it is not economically viable to make the trip from up in the mountains down to sell their coffee at the cooperative if it is a very small quantity and of poor quality.

“It’s clear that climate change impacts the poorest the most. We may see a division between farmers who are prepared for change, or who live in a fortunate climate, and those who are not and do not. Gone may be many a subsistence coffee farmer who just doesn’t have the resources to last through these changes,” explains Elster of Crop to Cup. An aggressive cycle of diminishing yield from climate change leads to lack of capital to invest in the farm, which leads to more susceptibility to climate problems, leading to more diminished yields—and the cycle continues. Chigounis adds, “I see more farmers stuck in poverty and failed farms because they don’t have other avenues to pursue. They’re second-, third-, fourth- … generation farmers who don’t know where else to go.”

Climate change is more than just environmental and socio-political problems. Elster succinctly states: “Climate change is local, global and difficult to articulate. But wherever we go, farmers seem to believe that climate change is real, and noticeable within their lifetimes.”

This is the first part in an ongoing series devoted to educating the coffee professional about the changing climate at origin, highlighting new developments and trends in the ongoing battle threatening to destroy our industry. We will be exploring the new F1 hybrids from WCR and ECOM, as well as perspectives from Q-Graders and agronomists on these hybrids and other proactive measures to keep our coffee delicious and bountiful. Stay tuned.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Erika Vonie is a certified Q-Grader and the director of coffee at Variety Coffee Roasters in Brooklyn, N.Y. She has an active, participatory interest in current news regarding climate change, agronomy, and environmental structure in countries of origin.