We attend a Chanoyu (tea ceremony) in Uji, a small town in Japan famous for its matcha.

BY TANYA NANETTI

SENIOR ONLINE CORRESPONDENT

Photos by Tanya Nanetti

In the years I spent working behind a specialty-coffee counter, I had the opportunity to witness the rise of matcha. Within a decade it went (at least in Europe) from being somewhat unusual to becoming a new health trend. I realized that surely there was much more to know.

Going To Uji

While in Japan, I decided to make a brief stop in Uji—a small town near Kyoto often described as Japan’s “matcha capital“—which seemed like the perfect place to deepen my knowledge of matcha. There, apparently, everything was matcha-related: old teahouses selling expensive and rare matcha, tea ceremonies held almost everywhere, matcha cookies and ice cream, even bowls of ramen and gyoza dumplings that included matcha in their ingredients!

We decided on a Chanoyu (tea ceremony) at Taiho-An, the Uji City Tea Ceremony House. It sounded interesting, easy to book, authentic, and affordable: exactly what we were looking for.

On a warm spring morning, a short train ride from Osaka brought us to Uji. We took a long walk along the river, admiring the cherry trees in full bloom, and visited the beautiful Byodo-In, a majestic Buddhist temple built more than 1,000 years ago. And we couldn’t resist trying a delicious matcha ice cream.

Finally it was time to make our way to Taiho-An to learn more about Uji’s pride and joy, its famous matcha that is often considered the highest-quality matcha available.

Before the tea ceremony, we took a few minutes to chat with the nice lady at the Taiho-An counter, who explained how matcha came to Uji and why it became so popular.

Matcha Makes Its Way to Japan

“The origins of matcha can be traced back to China where, in the seventh century, tea leaves were steamed and pressed into bricks for easy transportation and trade,“ she said. “But it was a few centuries later, in the 12th century, that a Japanese Buddhist monk named Eisai returned to Japan after years of study in China, bringing with him Zen Buddhist methods of making powdered green tea and a handful of tea seeds.“ Once he reached Kyoto and its surrounding villages, those seeds, which were already considered among the highest quality in all of Japan, were planted in temple grounds. They thrived in the Uji area due to its unique geographic characteristics: fertile soil, close proximity to the Uji River, and a misty climate.

Not only is the tea special, but so is its method of cultivation. Around 1600, the method evolved from direct exposure to sunlight (which resulted in a sour, bitter tea) to cultivation in shady conditions for a few weeks before harvest. This results in the high quality and sweeter, more delicate flavor now associated with Uji matcha. Then, after harvesting, the tea leaves are steamed, dried without rubbing, and ground into powder.

From Ceremony to Commoners

In just a few centuries matcha went from being used for religious ceremonies in temples to being a luxury commodity, produced in limited quantities and reserved for the nobility. Gradually it gained popularity among the samurai class (who drank it to stay alert and focused), and finally among the general public.

Then, in the 16th century, a Zen student named Murata Juko brought together several fragmented pillars of the tea ceremony into a formalized ritual. The practice was soon made even more popular by Zen master Sen no Riky?, whose sons created the three main schools of the Japanese tea ceremony, which are still active today in continuing to pass on the knowledge of tea preparation.

Sen no Riky?, known today as the most revered historical figure in the Japanese tea ceremony, is considered the “father“ of Chanoyu (the way of tea). He was the first to describe its four basic principles: Harmony (Wa), Respect (Kei), Purity (Sei), and Tranquility (Jaku).

The Chanoyu

At that point, with a deeper understanding of matcha, it was time to begin the actual ceremony.

Led inside a small room, we took our seats as instructed and were immediately greeted by a small sweet treat, tasty and perfect to balance the intensity of the incoming matcha.

Then the Chanoyu began. The tea master, in total silence, proceeded with a series of ritual movements. In a matter of minutes, she cleaned all the utensils, poured a generous amount of matcha into a large bowl, added hot water, and whisked it with an expert hand. Once it became frothy and slightly bubbly, she served it, repeating the procedure for all the guests.

Once the matcha was drunk, the guests tried to repeat what the tea master had done, whisking and drinking our ceremonial matcha. Even after following all the steps exactly, the matcha was still completely different from the one prepared by the tea master! We realized that even the smallest change in movements made a difference in the outcome; there was certainly much more to learn.

A Way of Life

Once the ceremony was over, we returned to the main hall, delighted by the experience but eager to learn more. After all, as our host concluded, the tea ceremony is not only about drinking tea: “It is a ceremony that encourages mindfulness and a sense of tranquility, a way of life and a reflection of the philosophy of Zen Buddhism, a practice that changes following the changing seasons.“

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Tanya Nanetti (she/her) is a specialty-coffee barista, a traveler, and a dreamer. When she’s not behind the coffee machine (or visiting some hidden corner of the world), she’s busy writing for Coffee Insurrection, a website about specialty coffee that she’s creating along with her boyfriend.

Subscribe and More!

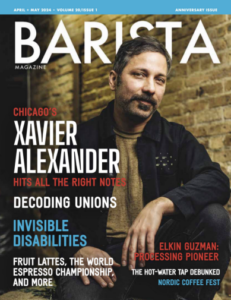

Out now: It’s the April + May 2024 issue of Barista Magazine! Read it for free with our digital edition. And for more than three years’ worth of issues, visit our digital edition archives here.

You can order a hard copy of the magazine through our online store here, or start a subscription for one year or two.