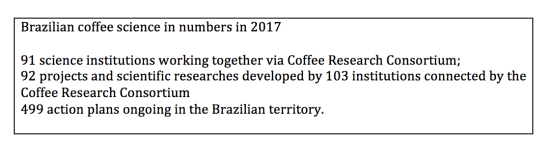

The creation of the Mundo Novo and Catuaí varietals, along with investment in a DNA bank with live coffee plants are some of the biggest accomplishments of Brazilian scientists in the last century. We break down the history of coffee science in Brazil, and focus on current research.

Photos courtesy of Emprapa Cafe.

Few people are aware that Brazil has spent more than 100 years studying the science of coffee. It all started with the Portuguese emperor, D. Pedro II, who decided to invest in technology to assure that his main lucrative product—coffee—would keep its producing fruit in high levels. Investing money in coffee science might have sounded silly a hundred years ago, but it put Brazil as a leader in the world coffee production quickly.

The Agronomic Institute of Campinas, known as IAC, was created in the countryside of the São Paulo state in 1887 and a special unit within the institute dedicated exclusively for coffee began in 1932. “Called the General Plan for Coffee Studies, this division was responsible for giving technical assistance in the fields in order to guarantee the coffee production development,” explains Dr. Gabriel Bartolo, the General Manager at Embrapa (Brazilian Agricultural Research Corporation).

The focus of coffee scientists hasn’t always been the same, and has shifted as time passes. For starters, productivity per plant was the main goal. With time, techniques that reduce production costs and new ways to fight plagues and diseases were the focal point. The creation of Biological Institute of São Paulo (Instituto Biológico de São Paulo) is one example of that. According to the Institute’s general director, Mr. Antônio Batista Filho, the state of São Paulo invested in a lab and a coffee plantation in 1924 in São Paulo city, with the main goal of controlling the coffee borer beetle, which colonized and destroyed coffee cherries.

Since then, Brazilian scientists have done a lot for technological advancement in the coffee industry. The main scientific findings that changed coffee production are:

- 1952: Mundo Novo varietal was launched officially by IAC

- 1955-1974: Mundo Novo is planted en masse and the Brazilian government starts a national plan of coffee renovation in every single corner of Brazil

- 1970: Catuaí officially launched by IAC

- 1972: Catuaí starts being planted in the country

- 1975-1989: New mechanic equipment for post-harvest processes were developed and used by some producers

- 1990-2000: Great expansion in irrigation technology, which makes it possible to farm coffee in regions that never had coffee plants before, such as east of Bahia, Araguari, Coromandel and Monte Carmelo in Cerrado Mineiro.

According to Dr. Bartolo, sustainability and quality are some of current targets for Brazilian scientists. There are also studies being conducted to elucidate the environmental effects of coffee production. “The main goal is formulate, propose, coordinate and guide strategies and actions of generation, development and coffee technology transfer until actual days. As well as to promote and support research and development and innovation activities,” concludes Mr. Bartolo. Some of the other subjects keeping Brazilian scientists busy are developing best practices in the fields of technological machinery, sensory quality, genetic studies, climate change solutions, and technical information about roasting.

Dr. Helena Maria Ramos Alves is just one of the scientists looking towards the future. “We don’t produce only commodity [coffee]. We also have quality coffee, specialty coffee with very diverse sensorial profiles,” Dr. Ramos Alves notes. She is an agronomic engineer at UFLA (Federal University of Lavras), and has a master’s degree in soil science also at UFLA, along with a doctorate degree in soil science and land evaluation at Reading University in England. She and two of her colleagues—Margarete Marin Lordelo Volpato and Tatiana Grossi Chiquiloff Vieira—are mapping coffee environments in Minas Gerais region through remote sensors and other technologies. Dynamics of land use, climate change and carbon emissions are among other topics of research.

Other scientists are looking to show the power that varietals have on the flavor of coffee. Gerson Giomo of the IAC and his team of researchers are hoping to show that flavor goes far beyond terroir or processing. After some genetic improvement in the plant and great care in the fields, some varietals are showing positive results even with low altitude and poor terroir conditions.

Food Engineer Terezinha Salva, also from IAC, is analyzing chemical structures in coffee after genetic improvement. “I am studying the chemical composition in different varietals that IAC is working/creating in the last years via genetic improvement to verify possible changes and how it affects the final beverage in the cup,” explains Mrs. Salva. She has worked with coffee for over 16 years and is also studying the differences between red and yellow colored cherries, and volatile and non-volatile compounds after a roasting process.

Overall, the work of all these scientists shows that coffee is more resilient and adaptable than we thought. “The studies possibilities are huge because coffee is present in every single Brazilian biome. It is naïve to think that all this diversity is labeled as a commodity with the very same profile for years,” concludes Mrs. Ramos Alves. Genetic improvements with arabica and conilon (referred to often as robusta) plants are being developed to increase disease resistance while still retaining both quality and high productivity. It is important to register that sensory quality is pretty new in this field, but that through historical precedent that Brazil has set in coffee science, and the continued work of coffee scientists in the country, that we will begin to see some amazing coffees adept at being grown in various climates, altitudes, and environments.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

As a journalist, Kelly Stein has written about coffee in South America for six years in local newspapers, magazines and also for international publications such as STIR Tea & Coffee Magazine. Based in Brazil, she loves telling stories from the biggest coffee producer in the world. To follow her coffee/gastronomic adventures, follow her at Instagram: @kellinhas.