Peru produces the most organically grown coffee of any country, and yet their coffees are still not seen on many specialty coffee menus. One barista shares his experiences working with the Pangoa Cooperative and how the co-op has given support and strength to producers in the region.

There are coffee regions we know well, but there are regions where violence, accessibility, and poverty have detrimentally affected coffee production. In this ongoing series, we’ll highlight different coffee-producing countries and discuss the struggles producers face and how activists, baristas, and various non-profit organizations are helping to make coffee from these countries viable, more profitable, and available to a wider market.

BY JACKSON O’BRIEN

SPECIAL TO BARISTA MAGAZINE

All photos below courtesy of Peace Coffee. Cover photo courtesy of Henry Gines.

As the Head Barista for Peace Coffee, I spend most of my time talking about coffee: brew ratios and extraction levels, helping our retail and wholesale customers get the best out of our coffee at home in Minneapolis. September was different—I had the chance to visit a coffee cooperative in Peru with Felipe Gurdián Piza from Cooperative Coffees.

Peace Coffee has been buying beans from Cooperativa Agraria Cafetalera Pangoa in San Martin de Pangoa, Peru, since 2005 and their coffee is a main component of the espresso blend we brew at our four coffee shops. A trip to origin meant meeting a few of the growers. Plus, I would get to explore and learn about coffee production in a country that produces a large amount of the world’s organic coffee beans.

After arriving in the port city of Lima, I wanted to experience a bit of the city before I headed to the coffee farms in the mountains. I wanted to find a place to get a cup of coffee. Traditional coffee in Peru is prepared using a stove-top apparatus that looks like an Italian coffee maker. The water is poured from the top and drips through the coffee grounds, ending up in the lower part as a highly concentrated syrup. When you’re ready to drink the coffee, you just add water or milk to the concentrate. But coffee culture is changing in Peru and now you can find the same kind of pour over and espresso machines I’m used to in the States. I had my first cup of coffee—a delightful Chemex—at a little café called Kaldi’s, where coincidentally, they served coffee from the Cenfrocafe co-op, another source of Peruvian coffee for Peace Coffee. That evening, I boarded my overnight bus to San Martin de Pangoa.

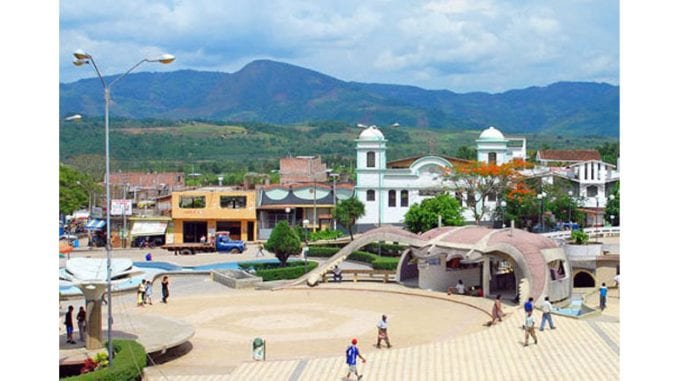

San Martin de Pangoa consists of twelve square blocks of houses, stores and restaurants surrounding a park at the town center. The road going into and out of town is paved. Every other road is made of dirt and rocks—they kick up a ton of dust. The roads are filled with pedestrians and dirt bikes (some of which have been converted to two-seater taxis) and dotted with pickup trucks.

I walked the five blocks to the co-op and the first thing I saw in the office was a storage locker with a pair of Peace Coffee magnets on it, mementos from previous visits. I met co-op general manager Esperanza Dionisio Castillo, assistant manager Albino Nuñez and co-op board president William Vasquez Diaz. Over the next few days the three of them would show and tell us everything we could ever hope to know about Pangoa coffee production.

At the warehouse we learned of the logistics of how coffee is bought from the farmers by the Pangoa co-op. The majority of the coffee delivered to the cooperative by farmer members is partially dried parchment, and the drying process is finished on the co-op’s patios. The coffee will then be cupped and graded by staff of the cooperative. The parchment coffee will be judged for how much green coffee it will produce (typically around 75 percent of the weight) and sorted into one of four categories: specialty organic (cupped above 80 points), specialty conventional, commodity secondary organic (cupped below 80 points), or commodity secondary conventional (which pays the least).

Farmers can opt for a higher initial price without the possibility of profit sharing at the end of the year, or they can opt for a lower initial price and if the co-op posts a profit at the end of the year, they get to see their share of that profit. The co-op tracks how much each farmer is producing, when they harvest and sell to the co-op, and what their quality levels are year by year. This information allows the cooperative to communicate what quality will be coming—and when—to clients such as Peace Coffee as well as estimate future sales.

In addition to handling coffee beans, Pangoa Cooperative has a small café set up next to their business offices. It’s a place where you can purchase goods — coffee beans and beverages, along with chocolate and honey — from the co-op. It’s also a way to get young people in the community involved in the co-op as baristas.

I started the training with espresso coffee preparation, milk steaming and machine maintenance and cleanliness. Because I was in a farming community, the time that I would normally spend talking about seed-to-cup stuff was spent on more advanced extraction. There was a language hurdle, but Felipe stepped up to translate where my Spanish was lacking. Another challenge was that the milk in their cooler didn’t steam properly. It produced giant soapy bubbles no matter how the steam wand was placed. We purchased a few cartons of additional milk and eventually settled on a concoction that worked. One of the baristas considered contacting a friend of his who had a cow as a source of fresh milk. I almost took him up on it, but what good is it to teach people how to texture raw milk if they can’t do it regularly?

The training day ended with a tasting of the locally roasted coffee, which was delicious. It’s cool to think that a single community can have the skills to grow, process, sell, roast and brew excellent coffee. The beans are going from seed to cup in a matter of days and within 20 kilometers.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Jackson O’Brien has worked in the coffee business his whole adult life. He is the Head Barista at Peace Coffee in Minneapolis. When he’s not making drinks, Jackson can be found drinking beer, cooking, finding new and interesting foods to eat, listening to socially irresponsible metal and/or rap music, finding the newest cat videos on the internet, going on adventures with his wife, playing music with friends or family, or playing croquet.

Amazing story, thank you so much for sharing! It seems like the Pangoa co-op have a really great business and farming model going, which is great for both the farmers and the buyers, their dedication to quality and their variety is very impressive. Why do you think Peru isn’t very well known as a coffee region even though it evidently produces the most organic coffee, and at a very high quality?