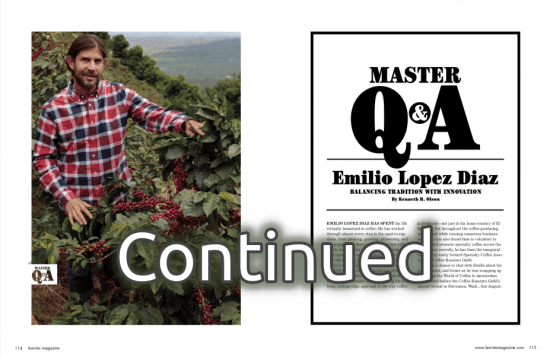

We were lucky enough to interview El Salvador’s multi-talented Emilio Lopez Diaz—coffee producer, retailer, roaster, and so much more—for the Master Q+A feature in the August + September 2018 issue of Barista Magazine. As often happens when we talk to longtime coffee professionals, they have so much more to share than we have room to print in the magazine. Today we continue our Master Q+A session with some of the great stuff that didn’t make it to print. This is Part 1 of our continued conversation. Part 2 will be published soon.

Kenneth R. Olson: When you were a kid, did you think you would be working professionally in coffee as an adult?

Emilio Lopez Diaz: Not really, actually. Coffee has been always part of our life, and I never really saw it as something that I would work on professionally. I grew up going to the farms with my mom, and coffee would always be part of the family conversations, but probably because we only had the farm and no mill or roastery, it was just not appealing as a business.

KRO: That’s certainly not the case any more. Can you tell us about all of the different businesses you are currently involved in with coffee? For example, you’re a coffee producer, but also involved in the Topeca roastery, right?

ELD: Indeed, in El Salvador we run a company called Cuatro M Cafes, and here we currently own and produce coffee at four farms, Finca Ayutepeque, Finca San Gabriel, Finca El Manzano, and Finca La Cumbre; these are located from 1,000 to 1,550 masl, and roughly cover an area of about 280 hectares. We also run a mill at Finca El Manzano that processes coffees from our farms but also from other neighboring farmers as well. It is through that company also that we export coffee from El Salvador to the U.S., most of Europe, Australia, Korea, and Japan.

Here in El Salvador we also have a company named El Potosi. It’s a company in which we have different lines of businesses. El Potosi runs Café Topeca in El Salvador, where we roast coffees from our farms and supply many cafés, restaurants, grocery stores, and hotels; in the last few years this segment of our business has experienced great growth. Along with the roasted coffee we offer coffee shop supplies like espresso machines, brewing equipment, etc. This year we also inaugurated our brand-new bottling line for our new beverage products also with the Topeca brand, although it will focus on cold brew, and soon will be offering other coffee-based drinks.

El Potosi, is also a distributing company that carries and represents different brands of products for the coffee industry. Some of these products include Pinhalense, the leading manufacturer of milling equipment in the world; here we supply other producers and millers with equipment for their operations in El Salvador. Pinhalense and us have a great relationship which includes the research, development, and testing of new equipment at our El Manzano mill.

Also in this company we distribute a brand of fertilizers, Yara, a Norwegian company which is the oldest and biggest in the world, and that offers the most clean and traceable sources of mineral fertilizers available in the agro-industry.

Outside of El Salvador, we also have other operations; for example, in the U.S. currently I’m involved in two businesses. Topeca Coffee, the roastery and the coffee shops which currently operate from Tulsa, Okla., is one, and I also own and run a sourcing and importing company called Odyssey Coffee out of Portland, Ore., focusing on direct-traded coffees from El Salvador, Guatemala, Brazil, and soon Ethiopia. This is my new baby, and I chose the name because of all the journeys I’ve taken, and how coffee has allowed me to travel the world and discover incredible places and relationships.

In Brazil, we co-own a coffee farm called Fazenda Santana; this partnership is very unique because it includes three partners very active in the coffee industry. On one hand, it includes Carlos Brando and his son Joao Alberto, who bring up milling equipment experience but also an industry scope that is incredibly rich because of their work around the world. On the other hand are Arnaldo Moraes and his son Joao Guihlerme, who are experts on the farming and nutrition side of the business with years of experience in the industry. And then there’s me; I focus on the sales and trading, and processing of the coffee we produce there.

Besides the businesses I run and co-run, I also volunteer a lot of my time to other institutions, for example the Coffee Roasters Guild and the SCA, and collaborate and work with CQI on their new Q Processing course that we teach at Finca El Manzano and Fazenda Santana.

So that is at the moment what I’m working on …

KRO: Do you remember your first trip to a coffee farm outside of El Salvador? Where was it, and what was different about it? Have you traveled to many producing countries, and if so, where? Which do you think are the most interesting and why, and which would you like to visit that you haven’t yet?

ELD: My first coffee trip outside El Salvador was to Honduras in 2003 and it was definitely an eye-opener, mainly because of how near that was to us, but also how differently things were being done at the processing and farming level.

I visited the Welchez operation, a brand-new mill at the time—super clean, organized, and intended for tourism—near the Copan ruins. That trip pretty much made me want to continue exploring how things were done differently at different coffee origins.

My second trip was to Guatemala, to the Antigua region, where I visited Finca Filadelfia, also another tourist coffee farm and mill. Those two marked for me the way I wanted to make our operation look, even though I’ve never been focused on tourism but only for hosting our customers.

My third trip was to Brazil in 2006 to visit the Pinhalense factory, farms, and mills; and it was there that I took a leap into the future of the production and processing of coffee. If it only could be combined with quality cherries, I would say … meaning, I had the quality cherries in El Salvador but did not have the technology nor the productivity they had. On that very trip, I said to myself, “One day I want to own a farm here.”

Another thing that really caught my attention in Brazil on that trip was the way I was hosted and how all the farm visits were organized; it definitely helped me put together a hosting model for my own operation.

I have to say though, the thing that really shocked me and really impacted me the most in Brazil was that I did not see poverty at all in the coffee-growing regions, unlike you see in every single other place in the world. I would say that is the greatest accomplishment of mechanization and not relying on cheap labor.

After those trips I’ve been to the following origins to see coffee operations: Guatemala, Honduras, Nicaragua, Costa Rica, Panama, Puerto Rico, Colombia, Peru, Brazil, Hawaii, and Ethiopia. Top on my bucket list of places still to visit are Kenya and Indonesia.

KRO: You work with coffee on farms in multiple countries and environments. What lessons have you learned from your travels and experiences coffee farming in different countries and communities?

ELD: The first thing that comes to mind is how everyone is doing things differently, even from one neighboring farm to the other. This could be a good thing in some cases, but in most I have seen it as one of the biggest problems farmers have. I really do not understand how a farmer that sees that their neighbor is having success at one farming method, pruning style, or using certain fertilizer, or equipment, etc., doesn’t replicate or emulate what they’re doing.

To be honest, on the contrary, I have tried and applied pretty much every farming method, processing style, or trick that I see has been successful for others in my own operation.

I remember the first time I planted coffee trees without shade in El Salvador, everyone would say, “Oh no … that can only be done in Brazil! They have a different weather, latitude, varietals, etc.” Or when I began doing naturals in 2003 in El Salvador … “No, what are you doing, you are ruining the coffee, tastes like ferment.” And I could keep going, on and on …

So what have I learned from farming or collaborating with other producing areas around the world? Everything can be applied to your own operation; you just have to adapt it to your own reality, or your own circumstances. And then, the other thing is: The only way to know if it can be done or not is by doing it yourself in your own farm.