We keep going with our ‘Master Q+A’ with Scott Conary from the April + May 2020 issue of Barista Magazine, as he discusses the beginnings of barista competitions, their impacts on café culture, and how they have changed.

BY KENNETH R. OLSON

BARISTA MAGAZINE

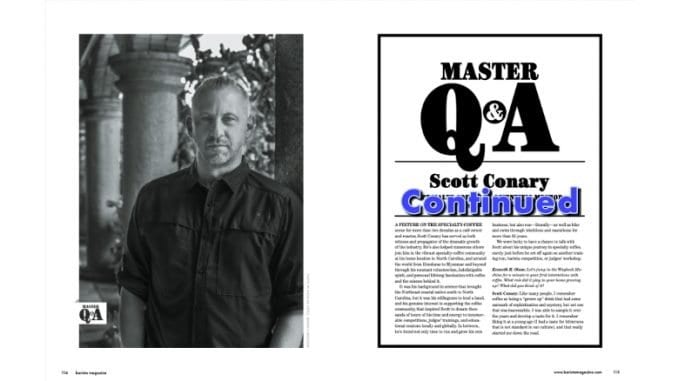

In our April + May 2020 Fifteenth Anniversary issue of Barista Magazine, I had the opportunity to interview Scott Conary for our “Master Q+A” feature. Scott has spent the better part of two decades as a barista competition judge, and in the course of our interview, he had much more to share about the competitions and their evolution than we had room to fit on the printed page. As we wait for barista competitions to resume again sometime in the future (and here’s hoping it won’t be too long), this seemed like a good time to share Scott’s thoughts and reflections on the growth and change he’s witnessed firsthand as a judge.

Kenneth R. Olson: Do you have any funny stories from your years of judging that would highlight how much things have changed from, say, 2003 to 2020?

Scott Conary: Recently, I and a few others have been digging into the archives to come up with some fun memories of the “way it was,” somewhat spurred on by the memory lane effort when WBC celebrated 20 years.

Looking at past scoresheets is a really interesting study in evolution, the things we thought were important (and they were, ostensibly, at first!) It reminds me that when we started, education was such a large part of what the competitions did. That won’t ever go away exactly, but how that education was implemented has changed dramatically.

The first step was to set standards and best practices that can be adhered to and scored. This was a big deal for the majority of folks who never took a class or were trained consistently, and a lot of the early years for comps were getting larger and larger numbers of people onboard to achieve those current standards.

Once that became better known (and disseminated widely through other outlets like Barista Guild of America certifications used as a jumping-off point from classes and workshops), the method of education and the focus of the competitions can be shifted to more exploratory and innovative. So instead of thinking that the competitions should mirror the real-world café setting, we were able to look at the competitions as a kaleidoscope of possibility—what is possible in our industry.

You can argue that for this next phase to be the most successful, it required that base of knowledge that the competitions helped spread worldwide. Now you can have a conversation with folks from around the world and not only agree but understand each other in terms of basic best practices.

With that established, the competitions can continue to evolve into an even better format for pushing the boundaries of what is possible in specialty coffee. And that is the part that everyone remembers: the new stuff, the crazy ideas, the innovations and demands by professional baristas to manufacturers to make better machines. Never before had there been such a response, in so short a time, to customer requests of ideas for improvements. So many of the things we take for granted now in our industry were forged in the fires of competition.

How important is it to get that score of six for coffee waste? So important that grinder manufacturers designed on-demand grinders. This wasn’t something that was being asked for specifically in cafés, but items like scales on and in drain trays, pressure, temperature, and flow rate, all of the various dose and distribution tools—all of these were pushed to creation from the desire for higher scores in competition.

I have a gift and curse for being able to wipe my memory clean between competitors and competitions. This probably stems from my scientific background and desire to remain as unbiased as possible, but what it means is, I often have to be reminded by friends who were there with me about all the crazy things we went through and drank.

It’s fun to remember that we required sugar, which we knew we would never use, at service, with the thought that we wanted to emulate a café setting. Or that all four beverages needed to be served at once (meaning there was a big boom in the tray industry for some time, until Stephen Morrissey showed us how to balance them all on our arms in 2008).

Are there any trends you’ve noticed over the years that may have started in barista competitions and have gone on to become common in retail?

So many! Methods of preparation, tools for dose and distribution accuracy (scales, OCD, and other distribution and tamping tools), investigation and insights into ratios and liquid weight (beverage volume) out.

Even just the aesthetic of an organized and clean station, as the “Knowledge” standard for presentation, has its origins in the competition. Modbar was just the next logical step for this open presentation format, where everything is being “judged,” and no hiding from the “technical judge/customer.”

A really fun thing to watch from the 1,000-foot viewpoint, and the luxury of seeing it for so long, are the stages that people, countries, and cultures go through as they get involved in competitions. Sometimes the simplest form is mimicry. This can have something to do with the advent of social media and the start of performances being viewed on video and YouTube. Often since the foundational things cannot be transmitted through camera (quality of beverages, balance of espresso, etc.), what people pick up on are the visuals … what people are wearing, glassware used, styles of presentation and speech. For a couple of years after Michael Phillips won [the World Barista Championship] in 2010, so many competitors in distant parts of the world were wearing suspenders, as if that was part of the secret to winning.

Are there any performances, signature drinks, or something else from competition that stand out to you in particular?

There are too many to remember clearly, but what stands out are moments when you can see or feel a groundswell of change—a pivotal moment when the game is changed, and people can tell.

Focusing on WBC champions, Michael Phillips took the judges to task in 2010 with a complicated signature beverage and comprehensive presentation that really put judges to the test. This was a bit of a wake-up call and kept our efforts in training judges moving forward to be sure not to be the weak link in this partnership we have with baristas for innovating our industry.

If a barista can manage something in the time provided, we as judges need to be up to the task of evaluating its merits. I remember judging this routine in the USBC finals (since I recused myself for finals at WBC), and appreciated the orchestrated way information was shared, such that one didn’t really need to take notes, but simply experience and absorb. This idea of a presentation that is so well done that simply by experiencing it the judge remembers everything, is my gold-standard definition for new judges when it comes to thinking about the level of what they have experienced.

And then there are the innovators. Folks who I have told them how much I appreciate their willingness to push boundaries and try something new on a stage that is merciless and might not score as well as something safer. But their desire to share this innovation is stronger, at least to some degree, than simply wanting to win (of course they want both). Colin Harmon is one of these people. Year after year he brought something engaging and chancy to the stage to the judges’ delight, I think with the knowledge that it might be difficult to score, and I made sure to thank him for continuing to push every time.

Both James Hoffmann and Stephen Morrissey showed us that a presentation did not have to be elaborate, but could be informative, insightful, and simply focus on delicious coffee. Alejandro Mendez and Raul Rodas took charge of the swing toward origin at the time, to really tie every aspect back to the coffee’s journey, often with a very personal touch, as the first two WBC champions to come from coffee-growing regions.

In terms of signature beverage patterns, I remember distinctly that around 2009 was the “year of the bacon” (which was specifically challenging for me, not eating red meat), and 2010-2014 had a significant rise in the use of cascara.

What role do you think barista competitions have in promoting the profession and specialty coffee?

The competitions have already gone such a long way in promoting and developing the profession of barista—from setting best practice standards that have influenced coffee professionals around the world (and made it easier to find delicious coffee almost anywhere), to increasing the exposure of the craft and profession—sometimes to a mocking level, but still raising awareness of the effort and skill required to do this thing correctly and thus engage customers worldwide in the idea that there is a value worth paying for. Naturally it’s not 100% effective, very little is, but the proof exists that a change has happened and continues to happen, and it allows more coffee shops and professionals to flourish than ever before for customers who are willing to pay for the increased quality.