The Producer to Producer Exchange Trip brings together farmers from Brazil to learn more about growing practices in Colombia, learning from their peers how to improve their crops.

BY RACHEL NORTHROP

SPECIAL TO BARISTA MAGAZINE

The second Producer to Producer Exchange Trip took place in Huila, Colombia, at the end of May. In late 2017, the agricultural support organization EMATER in Minas Gerais, Brazil, hosted its 14th annual cup quality competition, with exporter Atlantica Coffee sponsoring the prize trip for the winning producers from the four coffee regions of the state to travel to Colombia for the Producer to Producer Exchange Trip. For the Colombia trip, Ally Coffee—for which I am communications manager—and several of our in-country partners organized visits to farms, mills, and educational centers to facilitate cultural and agricultural exchange between coffee growers from the two neighboring countries.

A producer exchange trip is much different than a sourcing trip, voluntourism excursion, certification audit, press tour, or any other reason one might visit coffee farms and mills in the company of local experts. Watching and listening to what producers shared with each other, what information resonated with them and why, which questions they asked and the answers they received, provides a unique lens to view what matters most to those in the business of growing coffee. For the rest of us folks who are not landowners and do not have personal investments in agriculture, it is an imaginative stretch to put ourselves in the shoes of producers, and often we miss the mark in assuming what is important, despite our best intentions to make positive impacts at origin.

To help understand what it is like to work at other points along the coffee chain, here is a non-exhaustive review of current hot topics in South American coffee production as gleaned on the trip:

Not all cooperatives are created equal

After a quick stop at Ally’s new office in Bogota, our first destination was the Coocentral cooperative in the municipality of Garzón in the department of Huila. Coocentral operates like many of Colombia’s cooperatives: It has close ties with the Colombian Coffee Growers Federation (FNC), offers financial services for producing families, and has agronomical support on the farm, a central mill, and a member base of thousands of smallholder family farmers.

“They are very organized here,” observed Regivaldo Moreira Dias, an agronomist with EMATER. “We can see that here cooperativism is very strong. I think Brazil can learn from this type of organization.” In Minas Gerais, cooperatives are businesses more than smallholder support systems, and their members are also producers who run their farms as large agricultural estate businesses, not as modest family lands in most cases.

Non-farmer takeaway: Cooxupe is the largest coffee cooperative in Brazil (and the world) in Guaxupe, Minas Gerais. It exports more coffee than many producing countries. In contrast, Coocentral is one of Colombia’s largest mills, and the leadership knows the name of the producer delivering a load of coffee by horse-drawn cart. Cooperatives share administrative similarities in members’ ownership, but not all cooperatives are involved to the same degree in the day-to-day lives of their members.

Legal seedlings for sale

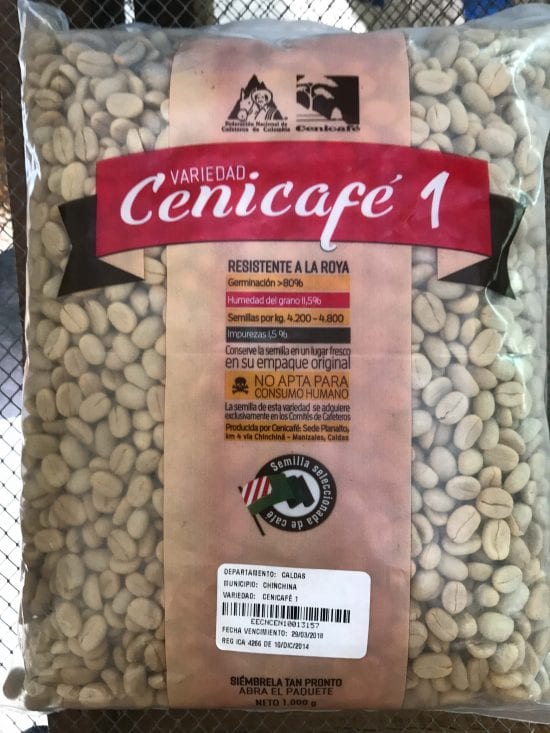

In Brazil, one farm cannot sell seedlings to another farm—to do so is illegal. All seeds are certified and must come from verified vendors to guarantee that they are clean and are in fact the variety they say they are. In Colombia, the FNC also offers certified seeds of the varieties developed at their research organization Cenicafe (the new Cenicafe 1 is pictured in packaging and as young planted trees with massive leaves). The group from Brazil was surprised to see that there are also many farms, like Finca Lusitania in Gigante, Garzón, Huila, that sell nurseries of coffee seedlings to other farms as a second source of income.

Non-farmer takeaway: While these days we list coffee varieties on packaging as straightforward attributes, varieties belong to the tricky realm of plant breeding, which, in coffee, is still far from an exact science. We visited Finca Monteblanco in San Adolfo de Acevedo in Pitalito, Huila, where producer Rodrigo Sanchez has found numerous varieties of trees on his farm, planted by his grandfather, and is still exploring what the original seedstock might have been and if there have been mutations or crosses that have occurred in the field over the past 30 years.

Cold fermentation

Measuring degrees Brix was something the group from Brazil had not seen before. Like all farms in Colombia, Finca Monteblanco experiences a year-round harvest, with flowers and cherries at all stages of maturation sharing tree branches for 10 months of the year. We squeezed mucilage from ripe, overripe, and underripe cherries into the reader to compare the amount of sugar in each. Rodrigo explained that the degrees Brix helped him decide how to best process the coffee, destining cherries with the highest degrees Brix to the cold fermentation he and his team developed.

“My first trip to Colombia was to Pereira, Quindío,” said Edson Tamekuni, winner from Cerrado Mineiro. “There, the land is totally different and farms are larger. Here [in Huila] I saw different methods than I’ve ever seen in my life, like cold fermentation.”

Non-farmer takeaway: Knowing what to measure and what to do with farm data is one of the hardest aspects of growing a crop. Should soil be analyzed by lot, or should all hectares be given a standard dose of macro- and micro-nutrients? Should cherries be harvested on a calendar timeline, when they look ripe, or when their degrees Brix hit a certain level? Agriculture is a bundle of variables, and even producers who have decades of experience still must ask hard questions about which data is worth collecting and how to use that information to produce the best-quality coffee—and the most of it.

But, beyond all its technicalities, coffee will always be personal, and that means there will always be opportunities to take a few ideas from here, a few ideas from there, and grow coffee with individual flair. Joaquim Adolfo Pinto Noronha, the manager of the winning farm from Sul de Minas, sums it up with one of his takeaways from the trip: “The way Colombians work with love really caught my attention. I think that’s a message we can pass to the world. It’s great to see other countries that produce coffee.”

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Rachel Northrop manages communications for Ally Coffee. She also covers Latin American origins, supply chain sustainability, and innovation across the coffee and tea industries as a freelance contributor to several publications.